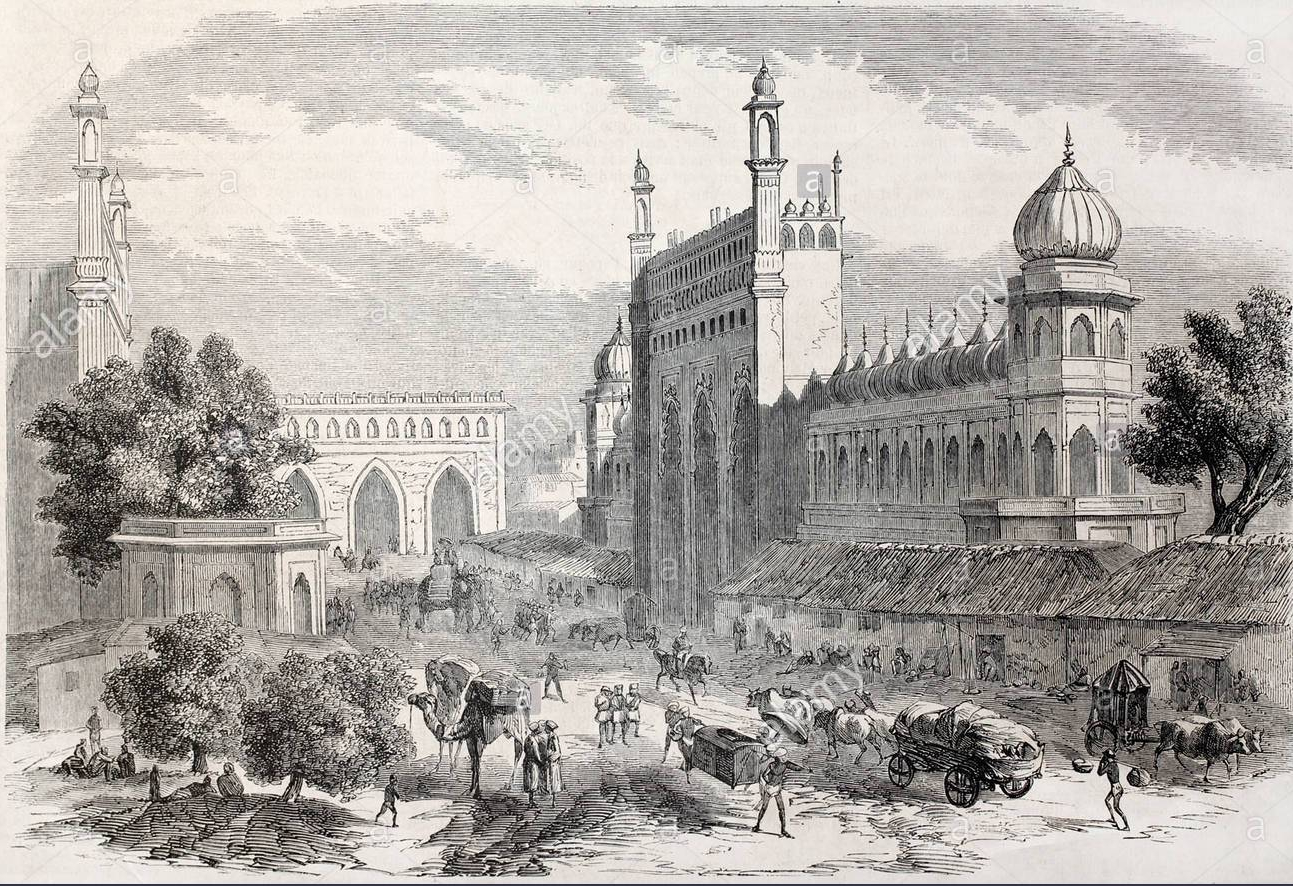

The Kingdom of Awadh (1732-1858), or as the British called it, Oudh, continues to evoke images of a society refined and sophisticated beyond any other. A syncretic melding of the best of Indian and Persianate-Turkic high cultures in all forms of art, architecture, music, poetry and intellect, even food and drink. This all too brief flowering of an elegant blend of cultural traditions was in actuality a long time in the making; the richly cultivated Indo-Gangetic plains were one of the cradles of early civilization, the site of the ancient kingdoms of Kosala and Magadha and the birthplace of Ram amongst many others. Cultural exchanges, trade and commerce with Persia and Central Asia were a constant feature throughout the ancient and early modern periods of history. The legendary wealth of India had always attracted migrants; often adventurers and fortune-seekers, some in search of kingdoms, some with ambitions of world conquests, still other less fortunate seeking refuge and shelter from war-torn homes and natural disasters. India’s abundance of resources was such that she was able to accommodate all. Early European writings about travel in India mention the ease of travel in a country which allowed considerable freedom of movement to foreigners.

Muslims have been a part of the Indian landscape almost from the early days of Islam. In spite of their negative depiction as fanatical aggressors by Colonial British and European historians and more recently by Indian politicians and popular media, India’s early encounters with Islam were peaceful and a mere continuation of the age-long commercial relationship that had flourished across the Indian Ocean from pre-historic times. The first mosque on Indian soil (and still in use) was built in what is now the state of Kerala, at Methala, in AD 629 by an Arab trader. The military conquests by the recently converted Turkic warlords was also a continuation of earlier militant incursions by Central Asian conquerors such as the Scythians, Huns and Kushans. Interestingly, early modern Indians continued to refer to Muslims as Turkusha, a term they had used for over a millennium for the nomadic invaders who came in from the northern passes.

Although small communities of merchants and traders from West and Central Asia had existed in India, pre-and post-Islam and peripatetic Sufis had slowly begun to make their way across the length and breadth of the subcontinent; the establishment of Muslim rule in north India encouraged a further steady and constant flow of scholars, intellectuals, artists, poets along with the merchants and soldiers of fortune. As in the past, war-weary refugees from Central and West Asia, only recently converted to Islam, also sought succour and sanctuary at the magnificent Muslim courts at Delhi.[1] Persian had long been established as the literary and court language at the Imperial courts of West and Central Asia and was so now at the Sultanate court at Delhi and later under the Mughals (1526-1857). As the font of intellectual learning as well as the vehicle for more mundane administrative purposes, its knowledge and mastery ensured instant employment in the vast administrative bureaucracy, as did military skills for displaced or aggrieved Turkic soldiers.[2]

India was the proverbial land of plenty that could embrace and accept all those who came seeking a better life for themselves and their families. This then was the route our ancestors took. Some came as refugees, some were wandering Sufis who laid root in the small towns of North India, others came as adventurers and sought service in Delhi or the many minor Sultanates and kingdoms that came and went with the vicissitudes of time. While some brought their families with them, it is likely that many did not and married into local families.

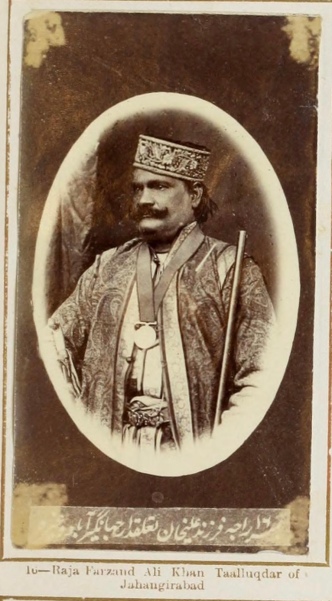

The antecedents of the Kidwais/Qidwais, the clan to which my father’s maternal ancestors the Jahangirabad family belonged, are fairly well recorded; Qazi Kidwatuddin, from whom the Kidwais/Qidwais trace their lineage is said to have been the brother of the Sultan of Rum,[3] Kaykhusraw, and the Chief Qazi of that Sultanate. A falling out with his brother forced him into exile along with his family. He arrived in India somewhere in the late 1190s and as a Turkish prince was well received at the court of the Sultan of the Ghorids, Muhammad Ghori. Qazi Kidwatuddin is said to have lead a fighting force and managed to win 52 villages in Ayodhya, which became his Jagir and came to be known as Kidwara. This is where he eventually settled down in 1205 in a locality which came to be later known as Kidwai Mohalla. His son Qazi Azizuddin married the daughter of Qazi Fakhar ul-Islam, the Qazi-ul-Quzat of Sultan Iltutmish, thus further consolidating his position amongst the established elites of the court at Delhi.[4] Qazi Kidwa died in 1208 and was buried in a graveyard at Ayodhya which was destroyed in the wake of the 1992 destruction of the Babri Mosque. The Kidwais/Qidwai’s remained firmly entrenched amongst the Ashraf or aristocratic gentry of Awadh, securing substantial estates and power, both secular as well as spiritual, since a number of clan members embraced the Sufi way of life, a tradition firmly rooted in the ethos of Indo-Muslim culture. Several members of the extended family continued to seek employment at the Mughal courts; a number were appointed qazis and others received mansabs, jagirs and sanads.[5] My father’s great-grandfather Raja Mardan Rasul Khan was a Risaldar or Cavalry Commander in the Nawab of Awadh’s army. His youngest brother Raja Farzand Ali Khan who succeeded to the estate of his father-in-law and kinsman Raja Razzaq Bakhsh of Jahangirabad[6] was a close associate of the last Nawab of Awadh Wajid Ali Shah. According to family lore when Awadh was annexed and taken over by the British in 1856 and the deposed Nawab chose (self) exile in Calcutta, he bequeathed four of his innumerable wives to the widowed Raja along with a Charbagh Palace to accommodate them. My father would relate how he had a vague memory of his mother taking him along on a visit to the youngest remaining Rani at that palace. He recalled her as an extremely pale-skinned, frail old lady; he was around four to six years of age, and the old lady most probably in her late eighties.

The Dewa family, my father’s paternal ancestors trace their origins back to Iran and claim a Syed ancestry. Their ancestor in India was Shah Ziauddin who arrived in India in 1398 as a member of Amir Timur’s retinue. It is said that scions of defeated noble and royal families whose lives had been spared were forced to remain in constant attendance on the emperor and thus under strict surveillance; basically, they were war hostages, albeit of aristocratic lineage. Shah Ziauddin was a scion of the Muzaffarid dynasty, a family of Khorasani origin that ruled Fars, Shiraz and Kerman from 1335 until 1393 when they lost their kingdom to Timur. After the brutal sack of Delhi, Timur realised he had far too many captives and released a number of his earlier hostages on the condition that they remain in India and not venture back to their homelands. The young Shah Zaiuddin made his way to Jaunpur, Awadh, where the former Tughluq governor, the Malik-us-Sharq (Master of the East) had set himself up as an independent ruler in the aftermath of Timur’s devastating conquest of north India and the destruction of the Tugluq Sultanate. It is the Sharqi Sultan who directed Shah Ziauddin towards Dewa with the bequest of a tax-free land grant or Madad-e-Maash. These revenue free properties were generally given to educated people to assist them in disseminating learning, particularly religious knowledge. The Dewa family took great pride in their scholarship and learning and produced several scholars as well as Sufis including Makhdoom Bandagi Azam Sani (d. 1465) the celebrated Saint of Lucknow who established a highly acclaimed madrassah in that city. In his hand-written noted my father mention that, “His tomb was situated on a huge big mound near the Telay Wali Masjid in Lucknow and could be seen from many places and many views in Lucknow. I hope it is still there”. Perhaps the most outstanding amongst them, the pride of the family, was Qazi Maulvi Abdus Salam/ Abd al-Salam, the Chief Mufti of the Emperor Shah Jehan’s army for many years, and a much-respected scholar and a Sufi.[7] Upon retirement from the court at Delhi he established a Darul Uloom at Dewa where the Maqulat or rational tradition of Islamic learning which encompasses philosophy, logic, arithmetic, geometry and astrology amongst other subjects was taught. Maqulat scholarship had gained momentum in India with the arrival of the brilliant Persian polymath and educationist Mir Fathullah Shirazi at the court of the Mughal Emperor Akbar (1542-1605) in 1583. According to S.M. Azizizuddin Hussain, “Ibn Sina and others perfected the combination of manqul[8] with maqul[9]. Fathullah Shirazi introduced this legacy in India. It was transmitted by a chain of Fatahullah Shirazi’s students. Mulla Abdus Salam Lahori (b.1540), Mulla Abdus Salam of Dewa, Shaikh Daniyal Chawarasi, Mulla Qutabuddin Sihalvi and Mulla Nazimuddin of Firangi Mahal of Lucknow”.[10] It was at the Dewa Darul Uloom that Mulla Abdul Halim, the father of Mulla Qutabuddin Sihalwi who set up the Farangi Mahal seminary received his training.[11] Abdus Salam’s son also served as a Qazi-ul-Quzat at Delhi during the Emperor Aurangzeb’s reign. Later, Syed Ahmed Khan, the nineteenth-century educational reformist would also prescribe to this rationalist approach in scholastic learning.

The educated families of qasbas like Dewa, Kakori and Fathepur took great pride in their use of chaste Urdu as opposed to Awadhi or Purbi which was spoken by the masses and the rural aristocracy such as the Jahangirabad family. Most people would, of course, shift seamlessly from one to the other as and when the need arose. My paternal grandmother only spoke Purbi, while all her offspring were equally comfortable in both, at least in their early years. My father and his younger brother who were both educated at Aligarh kept up the Dewa tradition much to their father’s relief.

The Muslim population of Awadh never exceeded one-fifth of the total population of that state. The Ashraf or landed gentry then was minuscule in number and consequently ended up marrying within that limited social sphere. Family lineage counted far more than material riches which explains the marriage between my paternal grandmother Taqi-un-Nissa, a daughter of the affluent Jahangirabad family, to my grandfather Mahmood-ul-Hasan, a scion of the substantially less wealthy but highly respected family of Dewa Sharif. Mahmood-ul-Hasan had the added benefit of being closely related to the acclaimed Sufi Haji Syed Waris Ali Shah whose Dargah at Dewa was a focal point of spiritual veneration in the entire district of Barabanki and beyond. Families who shared a bloodline with such Sufis enjoyed an elevated status, indeed some of the spiritual aura of the saint himself. It is therefore not surprising that the Muslim qasbas or market town which dotted the countryside in districts like Barabanki tended to centre around such holy shrines. More often than not ownership of land around the Qasba was tied to the land grants gifted to the saint’s progeny and kin. While larger landholdings were often a result of grants handed out to military men, or simply acquired by powerful individuals, the smaller taluqadaris and zamindaris were commonly held by families connected to daraghs. Moreover, the Darul Ulooms that were often attached to these shrines provided the essential education necessary for the advancement of an administrative service class that was the backbone of Imperial and state bureaucracy. Muslim laws of inheritance by their very nature resulted in the eventual fragmentation of landholdings and well-educated aristocratic or Ashraf gentlemen invariably sought employment either at the Imperial court or at the multiple smaller provincial courts that were a constituent element of the overall Empire. It is important to point out that it was not considered essential that the ruler be Muslim and service at the Rajput and other non-Muslim courts was not uncommon.[12]

With the disintegration and eventual demise of the Mughal Empire, many Ashraf gentlemen were forced to seek employment with the British, although reluctantly at first. The battle of Buxar in 1764 virtually ended native rule in India and the 1857 Revolt which also concluded in crushing defeat for the natives rang the final death knell. The reaction of the victors was merciless and brutal and the results were far-reaching and catastrophic. North India at the turn of the nineteenth century still bore visible scars of the 1857 war that had brutally ravaged its population, towns and countryside. The Muslim aristocracy were particularly affected by the crushing ferocity of the British retaliation for what they (the British) perceived as a ‘Muslim inspired’ revolt, although in reality the anti-British movement was far from communal and clearly cut through (perceived) religious lines with a leadership which ranged from Nana Sahib, the adopted son of the exiled Maratha Peshwa Baji Rao II, to the Rani Laxmibai of Jhansi, and Hazrat Mahal the Begum of Awadh. Ruins of palaces, forts and palatial havelis dotted the urban and rural landscape, most still inhabited by their now often improvised occupants.

The initial response of the British to the native uprising in Awadh had been to abolish the existing elite structure of the province, the taluqdari system under which the landlords or owners of estates, large and small, ruled as quasi-kings or rajas. Soon, however, the populace’s unremitting loyalty to their overlords and unwilling to change their allegiances forced the British to rethink their policy. The subsequent Taluqdari Settlement Act of 1859 restored the majority of the estates to their erstwhile owners and reinstated the taluqdars as landlords but stripped of their political, civil and military powers; many others, however, lost their lands which were granted to British loyalists from other parts of the subcontinent. This partial restoration of lost status helped, to some extent, in pacifying both the urban and rural elite although the humiliation and wounds of defeat continued to chafe and influence the attitude of the Indians towards their British overlords.

The British colonial objective was to squeeze the maximum amount of capital and resources from what had once been considered perhaps the richest empire the world had ever seen. Towards that end, they had systematically levied crippling and back-breaking taxes on all agricultural produce, and the revenues they extorted from all trade and commerce exceeded by far that levied by any previous native government resulting in an unprecedented number of man-made famines. Awadh, fortunately for its inhabitants, was somewhat of a late addition to the British Colonial Empire along with the erstwhile Mughal heartland. But in the early part of the twentieth century when my father was born and became aware of his surroundings, the British were not just merely in firm control of the province which they had renamed the North-Western Provinces and Oudh, but had successfully managed to convince a substantial number of the native aristocracy of the superiority of western culture and philosophy, even language, over their own. Persian, long the language of intellectual discourse and learning, the vehicle for prose, poetry and history, the instrument of governmental administration, and conduit of knowledge exchange within the wider regional world of Central, West and South Asia had been discarded by the Colonial administration and replaced by the newly bifurcated Urdu-Hindi. Traditional forms of learning at Madrasas and Dar ul Ulooms, the schools and universities that had educated scholars for centuries, were deemed inferior and downgraded to mere centres of religious knowledge and replaced by western-style schools and universities structured on the blueprints of Eton, Harrow and Oxbridge. In fact, the influence of Aligarh Muslim University on the aristocratic elite of the Indian subcontinent cannot be overestimated. Syed Ahmed Khan’s viewpoints and philosophies were deeply ingrained into the intellectual psyche of the men who attended his unique and innovative institute of learning. As a reformist but devout Muslim, his imprint on the young minds who imbibed the essence of Aligarhian scholarship was clearly evident in the views expressed by my father and his peers and widely accepted by members of the generation brought up in that social milieu. My father would often reiterate Syed Ahmed Khan’s pragmatic explanations of miracles as natural phenomena, Syed Ahmed “interpreted miracles naturally, making such an event as the parting of the Red Sea into a simple period of low water; the Prophets’ night ascension into a dream; the jinn into mountain dwellers.” [13]

These new institutions of learning proved to be incredibly successful in attracting the native aristocrats and moulding them into a hybrid mix of British-Indian gentlemen who often looked askance at their own centuries-old traditions and knowledge. This is not to say that everything held sacred was discarded in one fell sweep, but conflict and contradictions gained ground. Age-old manners, speech, clothing and lifestyles only gradually gave way to western norms, and that too largely in the male sphere of activity where interaction with the British was inevitable and necessary. The zenana of the women’s world continued to function more or less as it had done before British rule. My grandfathers on both sides of the family, for instance, continued to wear their traditional garb and were far more comfortable in Urdu as the spoken language, and both Urdu and Persian in their written forms, than in English. For my parents, this was not the case. For the Indian elite generation that came of age in the mid-twentieth century, traditional ways of life were more often than not considered “old-fashioned”, even archaic and undesirable compared to a westernised lifestyle that was considered “modern” and thereby far more attractive. Even everyday clothing and living patterns changed rapidly; the ubiquitous takht gave way to sofas and armchairs, and farshi or furniture-less living-rooms with their stuffed goh-takias, carpets, masnads and floor sheets were looked down upon as antiquated. The silver or gilded bed, which had always been displayed with great pride as prized dowry items only a couple of decades ago were now outmoded. Indeed, both of my father’s older sisters whose dowries had included what had previously been considered indispensable, gilded-silver beds legs, almost immediately discarded these old-fashioned objects in favour of “modern”, European-style wooden bedroom furniture. Men were quick to don European garb and although the women continued to wear their traditional attire, they now favoured European colours and patterns and materials over the brightly coloured silks and cottons of yore.

Through my father’s formative years these patterns were rapidly emerging. In the family homes, the gentlemen now often favoured a western-style drawing-room, amply furnished with highly polished teakwood or Sheesham Anglo-Indian sofas, chairs and innumerable tables. Decorative wall-paintings depicting flower-vases and often wine-bottles and small glasses, or intricate floral arabesque designs gave way to plain walls with western style paintings and large oil-painted portraits of the men in the family. In these spaces, they took pride in entertaining their British guests, the local administrators of the area. Even foreign architects were much sought after: Walter Burley Griffin, the American architect of the Lucknow University Library and a great admirer of Mughal architecture, was commissioned by Raja Ejaz Rasul Khan of Jahangirabad, my father’s maternal uncle, to design a new zenana addition to his existing Qila palace in Jahangirabad. However, the internal conflicts and contradictions persisted. My father often related how this maternal uncle, Ejaz Rasul Khan, an important taluqdar of the area had several European-style rooms in his palace in Lucknow; the crystal and glass drawing-room with furniture imported from Venice, the silver drawing-room in which the sofas, chairs and tables were covered with repousse silver over wood, the massive dining-room which seated a hundred people and had walls adorned with large paintings of his predecessors. All the rooms were lit by dazzling chandeliers and candelabras. Jahangirabad had at one point purchased the entire contents of one of two ships which had anchored at Calcutta, bearing priceless porcelain, jade, wood and enamel artefacts looted from the Imperial Chinese Summer Palace by the British. These were now displayed throughout both the Lucknow Palace and the Qila in Jahangirabad. All these rooms were used almost solely to host British dignitaries including the Governor of the province, yet when the Raja shook hands with a white man, he promptly placed his hand behind his back and availed of the first opportunity he had to wash it. Similarly, my paternal grandmother would shrink from receiving a peck on the cheek from the rare British lady who would visit the zenana section of her house. And while pale skin was considered both desirable and attractive by most Indian Muslims, the underlying pink tones of the European complexion was considered particularly unattractive to those earlier generations, an aesthetic perception that too underwent a change by the early mid-twentieth century.

The harsh treatment meted out to the Indians of North India, particularly Awadh and Delhi, by the British were still raw and those unpleasant memories still painfully fresh for most people some sixty years after the disastrous events of 1857. Oral narratives of the woes that had befallen family members in the aftermath of the doomed uprising were an essential component of regular and oft-repeated accounts and anecdotes that peppered the conversation in the zenana, in particular. These too were the stories told to the children by their maid-servants and attendants who regaled them with the heroic deeds of the male and female family members during and after 1857.

The bravery of the many hundreds of Kidwai men who had laid down their lives in both 1764 and in 1857 was widely lauded and mournfully lamented. The daring yet foolhardy and failed attempt by Raja Razzaq Bakhsh of Jahangirabad to blow up the British Officers lead by General Sir Hope Grant was an exceptionally popular tale and colourfully narrated. By early 1858 the British had consolidated their position in Lucknow at the conclusion of the unsuccessful native revolt; the countryside, however, took longer to subdue and contingents of the British troops undertook the task of ensuring the subjection of the ruling taluqdars and zamindars. When General Hope Grant arrived with his troops at the gates of Jahangirabad and made their way through the dense bamboo forest that surrounded his Qila, Raja Razzaq Bakhsh declared his submission and pledged his loyalty to the British, but a close search of his fortress revealed a couple of cannons well-hidden near the entrance, prepped up for firing.[14] These along with some discriminating letters sealed his fate. The old man had to beg forgiveness, but could not prevent the destruction of his fort by the British. Hundreds of similar mud and brick forts were destroyed by the victors and innumerable families left destitute, deprived of their properties and lands which was the source of their income. As a child, my father and his siblings would accompany their mother on her visits to her relatives, many of whom had been left impoverished in their crumbling mansions. One of the stories he narrated was about an old lady who lived with the remaining members of her family and retainers on one such derelict estate, the grandeur of its past still evident in the collapsing structure. It was widely believed by all that in in her impecunious state with no viable source of income this elderly relative was financially supported by a friendly Jinn who had taken pity on her and her family; every evening, after her Maqrib prayers, when she turned back the corners of her janamaz or prayer-rug, she would find a silver coin or mohar. This daily allowance kept the family reasonably solvent and allowed them to survive without handouts from their more affluent relatives. As an adult, my father figured out that it was not the supernatural visitor that kept them funded, but most probably a hidden hoard stashed away during the upheaval, that the old lady was privy to, the source and location of which she was obviously wary of sharing with anyone else and had therefore fabricated the fool-proof story of the benevolent Jinn. People had resorted to concealing whatever valuables they could in those troubled times, either by burying them in secret places, in bricked wall or floors, or in dire situations, throwing them into ponds and wells. These were age-old practices in the subcontinent. My father would confidently state that if the innumerable ponds, which were an integral part of the rural landscape were dredged and abounded wells searched, much jewellery and gold would be recovered.

Another narrative that particularly resonated with me was the tragic tale of a foolishly brave young man who with his bravado, and perhaps with an unfortunate touch of arrogance, refused to bow down to the victorious conquerors. The British administration in Lucknow had decreed that if a European and a native found themselves on the footpath at the same time, the native would have to step down and let the white man pass. Our hero, a Sheikhzada, the scion of the old, distinguished family of Sheikhs, the erstwhile rulers and governors of Awadh before the Nawabs, in his crisp muslin angrakha and wide-legged pyjamas, suitably scented with attar, his pure white, starched muslin cap set at a jaunty angle, must have found it below his dignity to step aside for one he perceived as an uncouth, unwashed Englishman and continued his dandified, yet elegant saunter until he was rudely pushed off the sidewalk by a walking stick yielded by a red-faced Englishman. Sputtering and cursing, the Englishman raised his stick and hit our refined young man causing him to stumble onto the muddy street. Picking himself up with as much dignity as he could muster in the face of his mud-spattered condition, ignoble condition, our hero drew his rapier, cunningly encased in his silver-handled walking stick and ran it through the shocked Englishman, then immediately recognising the enormity of his crime fled the scene post-haste. He rushed home to inform his newly-wed young wife about his calamitous encounter. Shouts and loud knocking at the gates confirmed their worst fear; the police along with the troops were at the door. The terrified girl, beside herself in fear, could only suggest he hide himself in her large dowry chest in the vain hope that the soldiers would not enter the zenana. That was not to be, and our young gentleman was hauled away for almost immediate execution. The fate of the widowed young bride is uncertain; some said she pined away for her handsome young husband and went to an early grave, others said she lived on to a ripe old age, telling and retelling her story, never remarrying, faithful to her unfortunate spouse till the end.

The upper classes of Awadh, like those elsewhere in India, eventually developed a love-hate relationship with the British and many sought to emulate their lifestyle and mannerisms. Elephants and horses gave way to the newly developed automobile, adorned and kept in the style of a horse or bullock carriage. There was even a local raja who bought an old, decrepit WWI plane and tied it to his front gates where the elephants had in earlier times been fastened. When asked why it was chained, he responded, “You can never trust those wily Goras and their inventions”. Although a good number of the Ashraf stuck to their age-old traditions, language and culture, material success and social as well as economic advances encouraged the more ambitious to model themselves on the British in as many ways as possible and this proved to be the guiding force which led to the subsequent Anglicisation of Indian society. Undoubtedly, admiration for the British, their perceived discipline, efficiency, administrative and military acumen continued to gain ground; most Indian were naively blind to the motivation behind the introduction of industries and particularly the railways by the British. They tended to believe that all this was being done for their (India’s) wellbeing and were incredulously unable to see that what they perceived as British benevolence was merely a tool to tighten the Colonial grip on Indian economy in a more ruthlessly efficient manner, as was their extremely successful policy of divide and rule along communal lines. My father and many, in fact, most of his peers in the military and civil administration, were amongst these admirers. Echoes of this and the distorted versions of our own histories, written and presented to us by Colonial historians and unfortunately, unquestionably imbibed by us, continue to colour our vision of our past and continue to influence our vision of our future, both in India and in Pakistan.

[1] The Delhi Sultanate was established by Muhammad of Ghor in 1192 and continued to flourish under various dynasties until the last wave of Turkic conquerors, the Timurid Mughals, established their empire in 1526.

[2] Turkic soldiers, especially cavalrymen and artillery gunners renowned for their military prowess, were in high demand in several non-Muslim kingdoms including the South Indian Imperial Kingdom of Vijaynagar.

[3] One of the Seljuk Sultanates in Anatolia, present-day Turkey.

[4] Mushirul Hassan; From Pluralism to Separatism. OUP, Delhi 2007. P 87

[5] Mushirul Hassan; From Pluralism to Separatism. OUP, Delhi 2007. P 89

[6] The Jahangirabad Estate had been conferred on that branch of the Kidwai family by the Emperor Jahangir, hence its name.

[7] … Mullå ‘Abd al-Salåm of Dewa, east of Lucknow, who was made mufti of the imperial army by Shåhjahån but who was also a philosopher. His student Daniyål Chawrasi, also from Lucknow, became, in turn, the teacher of Mullå Qutb al-Din, one of the most renowned Muslim scholars of the eleventh/seventeenth century in India. (Islamic Philosophy from Its Origin to the Present: Philosophy in the Land of Prophecy: Seyyed Hossein Nasr, 2006; pg. 206)

[8] The transmitted sciences such as tafsir (exegesis), hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) and fiqh (jurisprudence)

[9] Rational sciences

[10] S.M.Azizuddin Husain; Kanishka Publishers, New Delhi, 2005. P 32

[11] Francis Robinson; The Ulama of Farangi Mahall and Islamic Culture in South Asia, Permanent Black, Delhi 2001. P 43

[12] Two of my phupas or paternal uncles, the husbands of both of my father’s older sisters, Shaheeda and Hasina, Khan Bahadur, Sir Kazi Azizuddin Ahmed and his first cousin Khan Bahadur Kazi Khaliluddin Ahmed served as Diwans at the Rajput courts of Datia and Panna in Bundelkhand, Central India in the early years of the twentieth century.

[13] Barbara D. Metcalf; Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860-1900, Princeton Legacy Library, 2014. P 323

[14] Per General Grant’s own account, one of his sharp-eyed Sikh soldiers discovered the hidden cannons. P 268-270, “Incidents in The Sepoy War 1857-58, Compiled from the Journals of General Sir Hope Grant”.

Continued …

For our family, it is particularly tragic that my father was unable to complete his writings. He passed away suddenly, without pain or suffering, on January 19th, 2006, seven months short of his ninetieth birthday.

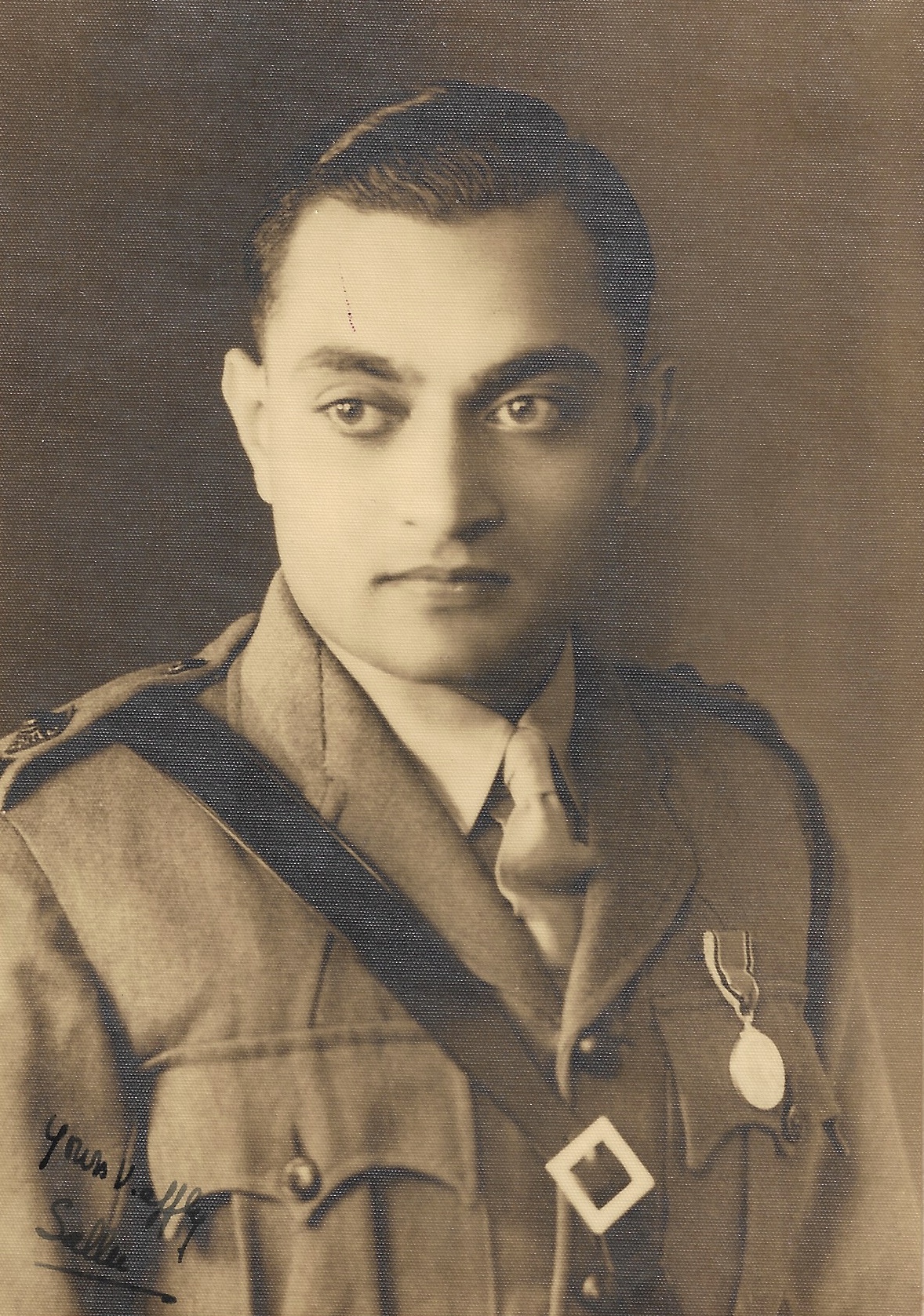

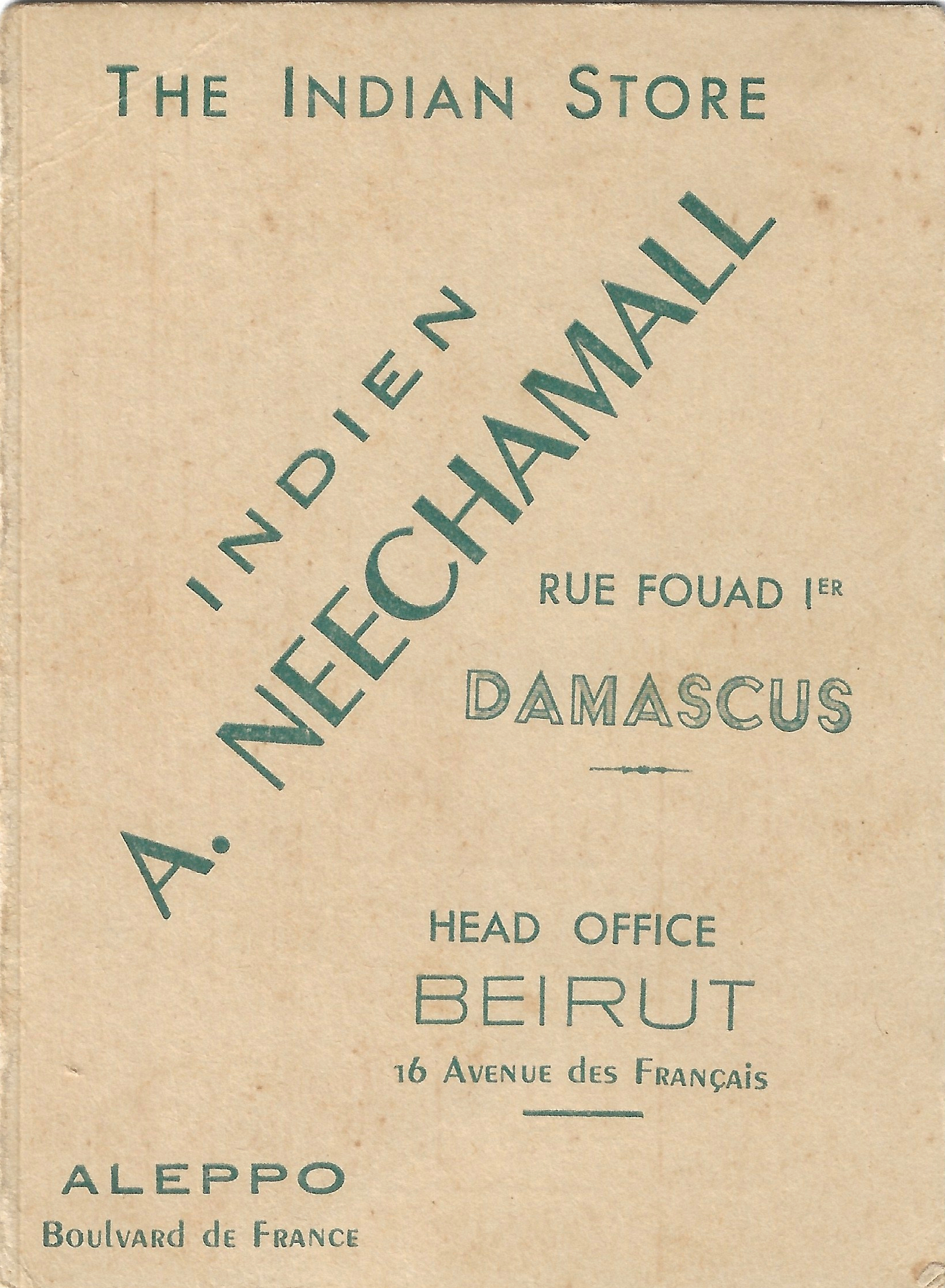

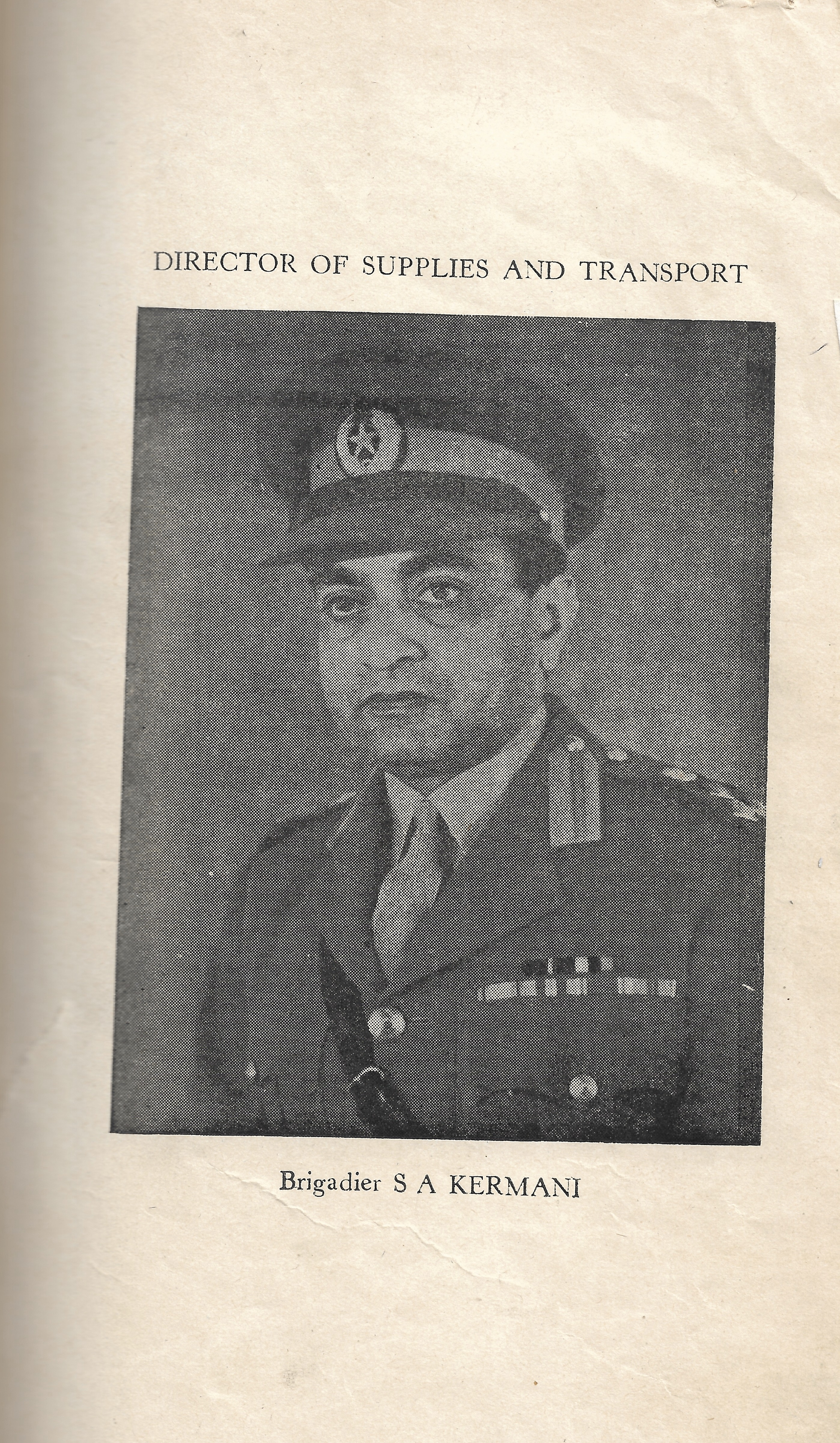

His memories stop midway in 1943, in Iraq, shortly after he had taken over command of the 52nd Base Supply Depot at Basra at the youthful age of 27. He remained in that part of the world from 1941 to April 1945 when he returned to India; a total of four years. Unfortunately, we have been unable to recover any further papers or records of his activities over those last two years in the Middle- East. What we do know is that he travelled fairly extensively, although he remained posted in Iraq throughout. He visited Egypt and enjoyed a private tour of the Grand Pyramids at Giza. He talked about the sophisticated people and culture he encountered in Lebanon and Syria, particularly Damascus and Aleppo, he dwelled on his visit to Palestine, to the holy city of Jerusalem where he felt blessed to have had the opportunity to pray at the Sacred Dome of the Rock Mosque. His deep interest in all matters spiritual led him to seek out the Padres of the various religious faiths and denominations that have long existed in West Asia. The balance and peaceful co-existence of the different religious communities and sects in Jerusalem was at that time exemplary. He told me about the two ancient Muslim families who have for centuries remained the guardians and protectors of the keys and doors of that holiest of Christian sites, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre the place where Jesus is believed to be buried. The Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Roman Catholic and other denominations all share the custody of the Sacred Church itself but the task of carrying and keeping the keys safe is entrusted to one particular family, while the task of opening and locking the doors falls to the other family. This has been the case for over five hundred years now dating back to the end of the Crusades and the rescue and liberation of Jerusalem by the Kurdish Sultan, Salahuddin Ayubi. The idea behind this being that no one Christian denomination can dominate or control the Church since the guardianship of the keys is vested in the two chosen non-Christian families. Very soon after his return to India in 1945, his much-loved father passed away on the 24th of May 1945. Of the three sons, my father had been closest to his father; their temperaments, interests and habits were similar. Realising that this son of his was the one most attached to their family history and traditions, to their lands and their home, he left the ancestral Dewa house to him. Unfortunately, the turn of events was such that he was never able to claim the house or the property that had been so designated for him to take over and run as a model farm on the family estate. In 1947 when he was given the choice to either remain with the Indian Army or transfer his services to the newly formed Pakistani Army he opted out for the latter. Logically it did not make sense; his senior officers cautioned him to rethink his choice; “Your roots are here Kermani, why do you want to go to Pakistan?” He was asked that question more than once by his British superiors. His non-Muslim peers also pressed him to stay on, “Don’t go, you have nothing to fear, you are one of us, you belong here.”. But he had made up his mind; his two older brothers-in-law’s, his sister’s husbands, both railway officers, had already made their decisions in favour of the new country. All the male family elders were gone by this time, his father, and both his maternal uncles and paternal uncle as well. Chotay Mamoon, Raja Imtiaz Ali had died much earlier, before the war at the age of forty-one, Baray Mamoon, Maharaja Sahib Jahangirabad, a patron and financier of the Muslim League passed away in 1946. Salahuddin Ahmed an energetic and enthusiastic young man was eager to serve the new country that came into being on the very day he turned thirty- one, August 14th, 1947. He felt Pakistan had a greater need for young people like him, more than the old country. That is how he always explained his selection, his decision to choose the Pakistan option. Of course, what he, and many others like him, did not realise at that time was how irrevocable and final that choice was. Even Mohammad Ali Jinnah planned on retiring to his luxurious mansion in Malbara Hills, Bombay, so my father can be forgiven for thinking that he could serve the Pakistani Army for a couple of years, hand in his commission and retire to his family home and lands in Dewa, Barabanki. But the umbilical cord had been cut, and there was no going back.

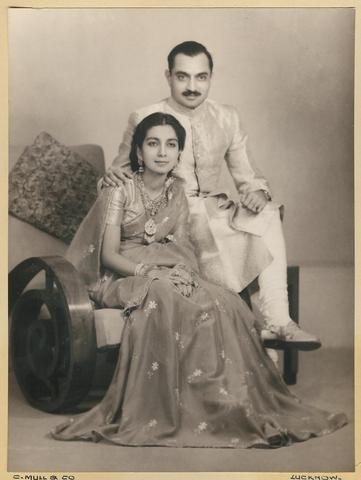

However, back in 1946 after my father returned from the war, plans were already afoot for his marriage. His mother and sisters were anxious for him to get married and settle down; he was approaching thirty, and most men (at that time) were married long before they got to that age. My parent’s families though not quite related, belonged to the same baradari; the Shurfa of Awadh tended to marry within a twenty-five to a thirty-mile geographic radius of their towns and qasbas. Matrimonial relationships between the Kidwais, the Dewa, Fathepur and Bansa families were long well- established, but in more recent years my mother’s Khala, Zehra Begum, had married my father’s first cousin, his Phupi’s son Wasiuddin of Dewa, and my father’s younger sister Murshida had married one of my Nani’s cousin Safiullah Siddiqui in Hyderabad Deccan. My eldest Phupi Shahida happened to meet my mother at Zehra Begum’s house in Lucknow and took an immediate liking to her. With Zehra Khala’s strong backing the proposal sent was readily accepted. The only condition my mother’s paternal grandfather, Masood Ali ‘Mahvi,’ the family patriarch put down was that my mother was to complete her Medical education before the marriage could take place. It was to be a long engagement, and a long-distant one too. In spite of my father’s request, my Nani would not allow him to meet or even see my mother. All he got was his sisters’ reports and a single photograph my Nani reluctantly agreed to send him.

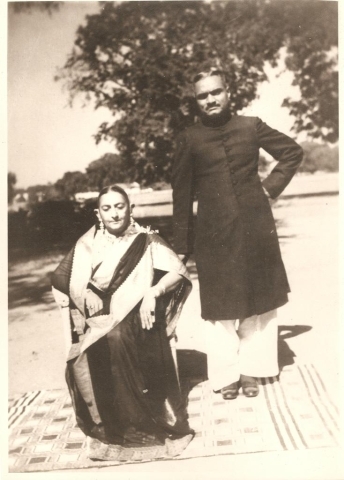

The two years my father spent in India before the division of the country were spent in Ferozepur, at the Training Centre, where he was posted as Commander Royal Indian Army Service Corps Training Battalion, and then in Bombay where he served as Deputy Assistant Director Supply and Transport, a position he held at the time Partition was declared. Major S.A. Kermani’s first posting in the newly established country was as Commander Royal Pakistan Army Services Corps in Dacca, East Pakistan, where the Chief of Staff Eastern Command was none other than the future General, Field Marshal, Commander-in-Chief, and President of Pakistan, Ayub Khan. It was Ayub Khan who advised the young man to not delay his marriage since travel prospects (to India) for Military personnel could soon become practically impossible. This startling news was immediately relayed to Barabanki and from there on to Hyderabad Deccan. Although Hyderabad was still an independent Princely State at that time, the likelihood of its survival as a separate domain surrounded by the Democratic Republic of India was bleak. The reality of the irrevocable antagonism between the newly created countries had sunk in and so the elders of the family reluctantly acquiesced, perhaps, cognisant of the improbability of my mother completing her medical education. The marriage date was fixed for April 3rd 1948. The baraat, according to eyewitness accounts, was elegant and impressive in spite of the unsettled times, and the bridegroom strikingly handsome in his Awadhi sherwani and churidar pajama. The young couple left soon after for Barabanki where the lovely young bride was introduced to her mother-in-law and the rest of the family; in those days, it was not the norm for the women of the groom’s family, particularly the senior ladies to travel with the baraat. For my mother, this was a world far removed from her urbanised life in the Nizam’s city of Hyderabad. Although she had regularly visited the north with her mother and siblings over the years and had numerous cousins and extended family in Lucknow, Paisar, and of course Bansa Sharif, her mother’s family home and qasba where a pilgrimage to the family Dargah of Syed Shah Abdul Razzaq was an obligatory requirement, her introduction to the still vibrant and dominant taluqdari life-style with its old-fashioned etiquette and customs gave her a glimpse of a culture which was at its very last stages of existence. The young couple was feted and feasted and taken to all the family shrines to pay their respects to their ancestral Saints.

As they prepared to leave for Pakistan, my Dadi generously suggested the newly married couple take their pick of fine carpets, the ubiquitous Gardiner Russian crockery, so popular at the turn of the century or any other items they fancied from the house. My father’s response was that they would do so when they came the next time, on a more relaxed visit. Little did any of them realise that the next time he would return would be thirty-two years later in 1980 to what was a tragic shadow of what had once been. The dynamic, effervescent, legendary Ganga-Jumna culture had been shattered and on the verge of being abandoned and lost.

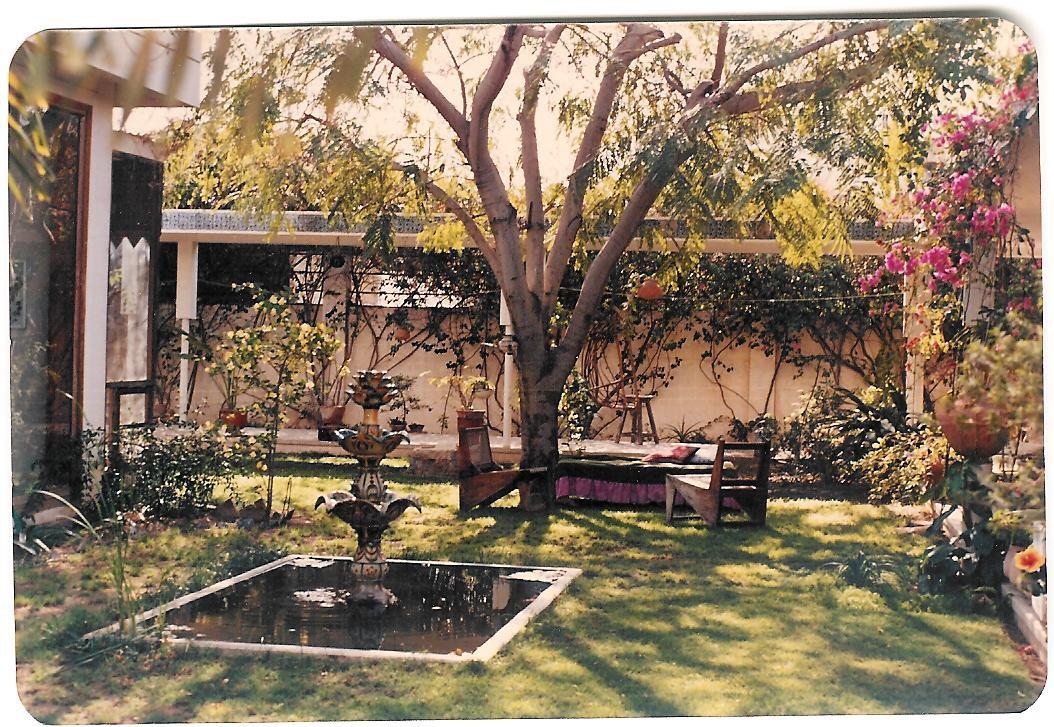

Life in the newly constituted Pakistan Army was on the whole agreeable. The Staff College in Quetta offered not just training for the officers but also camaraderie and social bonding. The Army Messes continued to run on the British pattern with ample wining and dining to make life enjoyable for the young officers and their wives. After Staff College, from 1949 to 1956 my father was stationed in Rawalpindi, then Lahore and back to ‘Pindi, a town he always liked and wanted to retire to. In 1956 he got his dream posting when he was entrusted with the task of setting up and establishing the Army School of Administration in Kuldana, in the beautiful Murree Hills. The location offered the perfect surroundings for a man acutely receptive and sensitive to nature, and his position as the Commandant of that institution allowed him to indulge in his life-long passion and quest to further enhance his environs. Truckloads of flowering bulbs, in particular, daffodils were planted along with strawberries and cherry trees in all the areas under his jurisdiction. His delight in gardening and planting was a deep-rooted passion, and every Army house we lived in, until 1967 when he retired from his last military post as the Director General Defence Purchase in Karachi, was enhanced and beautified by his gardening prowess. A lifelong member of the Horticultural Society of Pakistan, he served for several years as its President and throughout as an active participant. After his retirement from the Army, he served as the Chairman and Managing Director of the KESC, the Karachi Electric Supply Company, where his managerial skills turned an ailing corporation into what an International Development Bank recognised as the “Best run Public Sector Company” in South Asia. A strong believer in Cicero’s adage ” If you have a garden and a library you have everything you need”, his civilian life after KESC followed that creed. Travelling, reading and, eventually at our insistence, writing, and that too on a computer, when he was well into his eighties. A man of great personality and charm he was never at a loss for company; his innate ability to make friends and his capacity to maintain those friendships served him well up to the end of his life and even as his peers slowly passed away he continued to make new friends. After he himself left us, there was a constant stream of elderly gentlemen, whom he had befriended during his evening walks in the nearby park, who came to condole and share in our grief.

Salahuddin Ahmed Kermani left us without warning early morning on the 19th of January 2006. In December 2005 we had a large gathering of our (sadly) widely dispersed extended family in Karachi; my mother’s sibling and many of their offsprings, my father’s younger sister Murshida from Australia, altogether a wonderful assemblage of near and dear ones. Slowly over the first two weeks of January people started returning to the various countries and continents they now called home. I left Karachi for the USA on the 13th of January with a promise that we would all return in August to celebrate his ninetieth birthday. That was not to be. Five days later I was on a plane flying back, heartbroken, in total denial and disbelief. The Army and Corps Commander Karachi gave him a splendid sent off with full Military honours, the road in front of the house was blocked by KESC service trucks bearing as many workers as could be given the time off from work, people called from around the world and his friend’s widows grieved at losing a gallant and honourable support. He is buried in the dusty and barren new Military Graveyard in the Karachi Cantonment area, far from the verdant family cemetery in Dewa where his ancestors had been buried for well over six hundred.

Appendix:

Notes (from Salahuddin Ahmed Kermani)

MAULANA ABDUS SALAM DEWAVI

Maulana Abdus Salam[1] was one of the most respected and illustrious personalities of the Dewa family, so much so that his descendants came to be known as the Khandan-e-Abdus Salam. Stories and legends about this distinguished ancestor abound. The Maulana was a notable scholar and author of many books. Professor Abdul Majid Memon, the Chairman of the Department of Arabic during my university days, told me that in his opinion one of the finest Tafsirs[2] of the Quran was written by the Maulana, and that a copy of this Tafsir was at the Al-Azhar University at Cairo.

The Maulana’s exemplary knowledge and learning was widely acknowledged. An oft repeated family narrative was about an incidence that occurred during his days at the Imperial court of Shah Jahan in Delhi where he served as the Chief Mufti of the Imperial Army. The Emperor was a consummate builder responsible for the construction of the magnificent Taj Mahal, the Shalimar Gardens in Kashmir and Lahore, the Red Fort in Delhi, the Jamia Masjids in Delhi and Agra and the fabulous new city of Delhi, Shahjahanabad, besides many others. The Maulana was in attendance on one of the Emperor’s visits to a construction site of a new mosque. The older gentleman was slow in his movements and Shah Jahan called out; “Why Maulana, are you afraid of death?” The Maulana promptly responded; “Well Sire, indeed I am for if the Emperor dies another can immediately take his place, but if this Mufti dies it will be a long, long time before another can (adequately) replace me”. This judicious reply apparently pleased the Emperor and brought a smile to his face.

According to a family lore, no jinn can ever annoy a member of the Maulana’s bloodline. The story told is that a jinn fell in love with and took possession of a beautiful, unmarried girl much to the distress of her parents. The parents appealed to the Maulana who instructed them to arrange for a large karhai[3] filled with ghee to be placed on a large fire outside their house. As the ghee started to boil the Maulana began reciting certain duas[4] as a result of which hundreds of crows materialised out of nowhere and began to fall headlong into the boiling ghee until one of them appeared in human form and begged for forgiveness on behalf of his tribe and a solemn promise that no jinn would ever trouble any descendent of the Maulana.

On retirement, the Maulana returned to vatan, to the qasba of Dewa, where he established a Darul-Uloom. He is credited for having popularised the rational sciences or Maqulat in Awadh and passing on that Silsila of learning, fostered and advanced in the subcontinent by Shaikh Fatha Ullah Shirazi, during the reign of the Emperor Akbar, to the Farangi Mahal scholars of Lucknow.

[1] “… Mullå ‘Abd al-Salåm of Dewa, east of Lucknow, who was made mufti of the imperial army by Shåhjahån… “(Islamic Philosophy from Its Origin to the Present: Philosophy in the Land of Prophecy: Seyyed Hossein Nasr, 2006. Pg. 206)

[2] Explanation, interpretation, and commentary

[3] Wok

[4] Prayers

Lovely memories. I still remember the party my parents planned in our home Khiyaban in Lucknow to welcome the newly married couple Sallu and Meher in 1948.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Moin Bhai. I am sure that must have been a lavish affair.

Do you have any memories of my Dada’s death that you could share with me?

LikeLike

Thank you very much for the interesting last Chapter about Salauddin Bhai Murhoom.May Allah be kind to him in hereafter and grant him a high place in Jannatul Firdous. With lots of Dua Adeel Mamo

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Adeel Mamo.

LikeLike

Great people , interesting and beautifully worded family history

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike

You have done a great service to us all by sharing the life of this remarkable officer and gentleman with us. Truly worthy of an interesting book.

As a descendant of a Naval officer who migrated, it is uncanny how so many threads which wove our fathers’ lives, are in common.

The “Jazba” to serve Pakistan despite loss and sacrifice of family and ancestral lands left behind. Yet never looking back. Raising a young family. Serving the armed forces and living a life based on immaculate values and ethics. A life well lived, surrounded by friends. The cane chairs on the lawns never empty of friends each evening. The self planted garden and love of plants. I could go on and on. WE must compare notes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Nighat. Yes those gentleman were the product of a culture that embodied high moral standards and values which they imbibed and which formed the very fabric of their being.

Yes please lets meet up over a cup of tea and talk.

LikeLike

You were right in telling me to read the memoirs. Although I’ve just begun every single line is a pleasure to read.

LikeLike

I knew you would find it interesting.

LikeLike

Uncle Sallu was good dear friend of My father Choudhry Khaqan Hosain memoirs are very interesting glad to know all about his family/friends

.

LikeLike

Yes I remember Khaqan Chacha, my father called him Khaqan Bhai. Your family is closely related to my husband’s late Khalo Iqbal Athar.

LikeLike